Hotel California, Brexit and the European Experiment

Yanis Varoufakis, the former Greek Finance minister at the heart of the ‘bailout’ of Greece, has recently been addressing a number of groups in the UK after the publication of his book (“And the weak suffer what they must?”) about the experience and the implications of what followed.

Among the observations he makes in these meetings is that many complex, interrelated and interdependent factors make up what we know as the EU.

Europe is not ‘something out there, a thing that will always be there’. It is a vast continent-wide social and economic experiment that worked for a while, bringing greater prosperity and opportunity to hundreds of millions of people – and, as CDSM research has shown, a changing set of values.

Settler Driven needs have been largely satisfied for most EU citizens and levels of poverty formerly seen as normal have been largely eradicated. In this endeavour politicians and decision makers have proved a collective wisdom, even if some of the methods adopted led to some of today’s problems.

But as values research reveals, once needs are satisfied a new set of needs will naturally emerge.

Politicians have failed to understand that changing economic needs mean economic models must change to stay relevant; changing social needs mean the same for social needs models and changing values the same for values models.

Understanding the institutional and cultural changes that must be made when one need changes is often fraught with high political resistance. Two changing needs makes a satisfactory outcome unlikely - and having to deal with three is another level of complexity all together.

Further, the interdependence of these factors introduces indeterminacy as a major factor in politicians’ models of understanding.

What this means is that the methods and institutions that proved successful in satisfying a largely Settler driven society - as most European nations were during the immediate post WW2 decade - would not continue to ‘be successful’ in the minds of a values-altered electorate.

So how did we get here? The trauma of two major wars in Europe between 1914 and 1945 had reduced all countries in the original EU to similar states of being. For the most part the citizens of this ravaged world had always been Settlers - and those that weren’t were likely to have reverted to Settler as the future dimmed and the rigours of day-to-day life overwhelmed dreams and visions of a better tomorrow.

The vision of a better tomorrow was a Settler vision. The institutions that were created to be vehicles for delivering this vision were Settler organisations. Bureaucracy is a Settler way of ensuring that legislative will is carried out to the letter of the law. The democratically decided laws and judicially supported enforcement of them was a ‘belt and braces’ approach to life valued by safety-first Settlers. Conformity leads to safety – highly valued in the Settler world - and as a result the EU was constituted to create conformity.

But as Settler needs were being met through legislation and acceptance by member nations, the needs of satisfied Settlers were changing - and the definition of success was changing along with them.

The group that was re-defining success was the Prospectors - and their interpretation of success was very different. Their different needs would come to define what types of political, economic and social conditions would be popular or unpopular - what made them happy and, therefore, the type of politicians they would vote for and what they would expect from them.

As other academics and constitutional experts have written, the organisational framework of the EU did not reflect these changes in values. Its methods and structure stayed the same while the values of the electorate and their representatives changed; and legislation became a mixture of conformity (a Settler virtue) and deregulation (a Prospector virtue) often at odds with each other and ideologically powered by social forces not incorporated in economic models. This a classic case of culturally inspired organisational lag.

Within European organisations this ‘lag’ was observed as a fracturing and coming together of more political groupings than occurred in the early days of the Union. The environment became more complex – the same structure producing different results. But that complexity could still be defined as a struggle between morality and pragmatism; both in terms of what a desirable future could look like and also the most acceptable methods of creating that future.

A values clash is not necessarily a bad thing. Some of the side effects of achieving stability include social inertia, lack of innovation, feelings of discomfort among outgroups, for instance. The Prospectors desire to ‘push the boundaries’ in most situations broke through a lot of inertia and led to greater innovation – politically, economically and socially. But they brought their own downsides with them - a desire to dominate, an excessive drive for material wealth and an unbridled hedonism.

In failing to understand how to balance these drives politicians and decision makers carried on behaving in a manner that suited the organisational goal of creating and passing legislation. But owing to the changes in values of the cultures that elected them, politicians were making decisions in different ways. The decisions were arrived at more from a Prospector ‘let’s make a deal’ than a Settler ‘let’s create a better world’ orientation.

By failing to come to grips with this changed dynamic in framing, setting, and passing legislation the organisation was totally unprepared for the emergence of a wholly new values perspective that would change the dynamics of decision making yet again – and create the junction at which the EU and the UK now standingstands.

Decision makers in both the EU and UK have failed in understanding that, just as a Settler need satisfied leads to individuals and cultures developing new needs and becoming Prospectors with their own set of unsatisfied needs, so too do satisfied Prospectors perceive a new set of needs and become unsatisfied Pioneers.

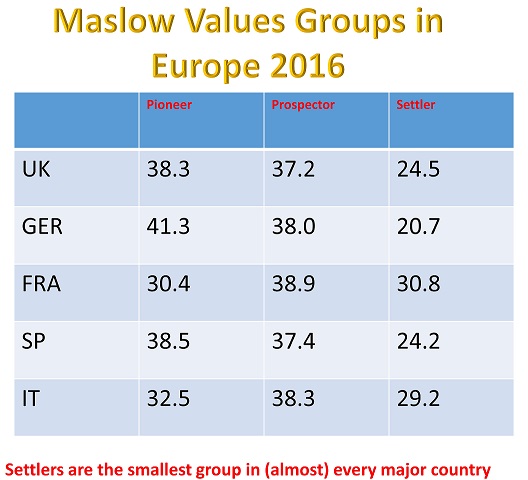

In the vast majority of major EU countries, Pioneers are now either the largest, or

second largest values group and Settlers are the smallest. A paradigm shift has occurred

with the success of the Settler-driven policies, but the seeds of destruction have been planted by the Prospector-led values –

and will bloom like flowers of evil - unless a new awareness emerges in this time of crisis.

The ever questioning Pioneers are asking the tough ‘why?’ questions at the moment – many of them rooted in an understanding that there are limits to what a deeply-rooted morality can help with in the complex and interdependent world of today.

For example, they question how a religion can act as a day-to-day guide for their own behaviours. Governments of (mainly) men are constantly questioned – and, as with established religions, found wanting. They question the value of an economic system that creates large disparities of wealth and legislation that gives unfair economic advantages to a chosen few while heavily taxing the poorer members of society; that comes up short in developing meaningful job opportunities for the young. They question the degradation of social systems that fail to meet their expectations of good education, good healthcare for themselves and their neighbours and good care for those most in need because of disability or infirmity.

They understand that their day-to-day guidance about how to behave comes from their own internal and evolving set of ethics – a product of their values system. Their values are not about belonging and safety or power and hedonism, but about transparency and truthful living. Politicians and organisations that can’t satisfy these needs will become natural targets for their desire to embrace seemingly quite radical change.

They feel they ‘need’ to give back to the society that helped them become the people they are today. They are natural activists – but do not find the EU is organisationally set up to hear their voices or to help facilitate and support their self-starting initiatives. Some departments within the EU might argue with this perception and, indeed, may have facilities that cater for Pioneers – but the perception among Pioneers is that the organisation is opaque and out of step with their ethics in a basic functional way.

This new factor creates conditions for even greater indeterminacy in social models – which impacts even more significantly on the premise of any economic modelling that promises greater clarity about outcomes in the economy.

Will the EU survive in this much more complex environment?

Many pundits are saying that the disintegration of support for the EU across Europe indicates it will not survive. Others see the disintegration as a necessary condition for the emergence of a changed form of organisation, and believe that the EU, its organisations and institutions, will not only survive but will thrive in a new environment. They argue that a changed electorate holding its political representatives to a new set of standards built on ethical responsibility and supported by improved openness, transparency of debate at the highest levels and much more community level economic exchanges is the future.

Economic reconstruction is unarguably needed to provide the circumstances for desired social changes demanded by Pioneer values.

Varoufakis would say that economic reforms are necessary – but not sufficient – for change to occur.

Armed with these insights, Varoufakis’s book and its recommendations should become even more powerful as a tool - to understand why Brexit is a storm in a teacup, and why the future of Europe will define the UK in the future.

Because whether Britain stays in or leaves and whether the EU survives or disintegrates the European experiment goes on.

As Varoufakis said in his discourse:

"The EU is like the Hotel California – you can check out, but you can never leave."