POWER. TO THE PEOPLE?

In one of the most unexpected outcomes in recent political history the UK Labour Party has attracted over half a million new, fee-paying supporters. After years of membership decline – mirrored by the decline in membership of most political parties – a spontaneous grassroots movement has sprung into being.

The Labour Party has been the recipient of this influx for two main reasons:-

1) a policy-led repositioning of its supporter base, and

2) its interaction with the Parliamentary Labour Party.

The new rules for Labour’s leadership election amount to, essentially, an extension of democratic rights and a representation of political thinking at a cultural level – within the body politic. Its first true exercise has proved a catalyst for the public expression of a ‘values war’ that has been simmering away for some time.

Regular visitors to this site will be aware of the values analysis of British politics and political parties that we have published for many years – based on empirical data, evidence from the British Values surveys in the relevant years. To those of you who have read the articles and reports the phrase ‘values war’ may seem obvious.

To new readers we offer evidence and comment on the reactions of the elite within the Labour party and the national media to the (surely) good news that the previously moribund Labour Party – losers in successive elections, with disheartened supporters and declining membership – has been revitalized and now provides a ready-made and re-energised constituency.

New supporters are expressing shared values with the values of core Labour voters – even though they have not contributed to the party through previous membership. This can be translated into a broad, popular movement that provides the Labour Party with a clear and distinct offering in relation to the present government.

What’s not good about this?

Rationally, the case can be made that this is the perfect time for change – when your organization has five years to build momentum. However, as readers of our research will know, each of the values systems in the UK experiences every aspect of life in different ways.

What for some is a clearly stated exposition of principles, and a set of policies based on the values of the party, becomes a threat to the identity, policies and principles of the party to another values system. Yet both claim to be the heirs to the legacy of the party and representatives of the future of the party in claiming back government.

In previous articles we have shown various aspects of the values research we use to analyse and clarify these confounding issues – why ‘white’ to one group looks ‘black’ to another – but the one very clear factor we see being played out in this particular values war is the battle for the dominant narrative within the party. That battle is between those driven by a need for power and those driven by a need for universalism and benevolence – as they see it, the purpose of power.

This is the most powerful clash of values in every society CDSM has measured in the last three years, and is seen in research across Europe and around the world as well as in other bodies of research.

This tells us that we are seeing a drama played out on a deep emotional level – not the level of economic ideologies or political philosophies, but at the level of individual values systems. CDSM is expert at measuring individual values systems – but to fully understand how individuals and groups of individuals interact in changing the dynamics of cultural values we have also taken on board a great deal of academic research and analysis. Thus, we can illustrate how and why small groups of people can become ‘extremist’ in their views - yet not fully comprehend how extremist their views are until their values-driven reality comes up against another values-driven reality and their views are challenged, refuted, disregarded or discarded.

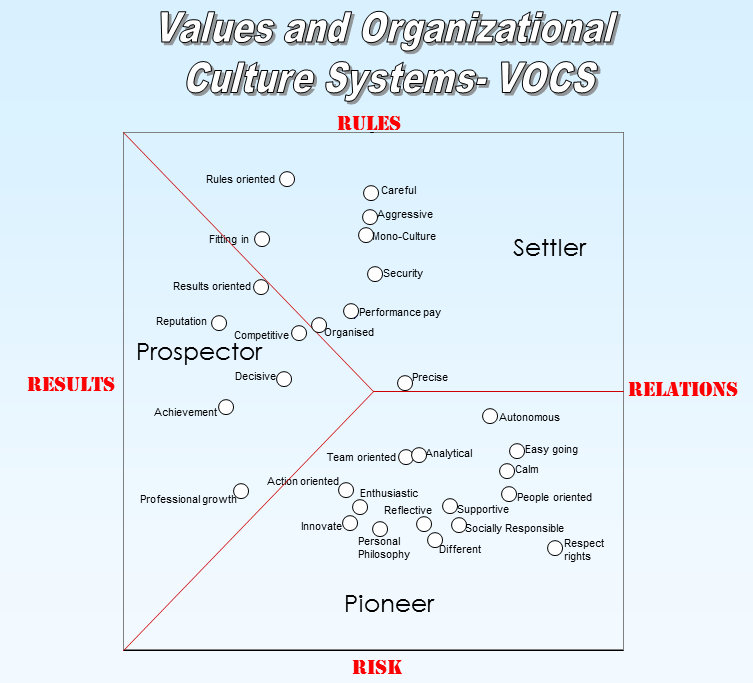

Right-click and select "View Image" to see a larger version.

Leon Festinger famously wrote about this in his seminal work ‘When Prophesy Fails’ and called this dynamic of competing realities ‘cognitive dissonance’. The research extends wider than the popular definition often bandied about in popular media (mostly concerning individuals) but the main thrust is that, until the dissonance is recognized the extreme version of reality as opposed to the mainstream is not clearly perceived by individuals or the groups that support the mode of thinking.

Cass Sunstein, one of the originators of ‘Nudge’, wrote an influential book called ‘Going to Extremes’ back in 1999, before his fame was established. In this academically driven tome, subtitled ‘How Minds Unite and Divide’ he lays out case study after case study of group cognitive dissonance and in the process redefines Irving Janis’ concept of ‘group think’ into a demonstrated theory of group polarization.

Values research is capable of defining the nature and extent of different forms of individual and group cognitive dissonance within any culture – through the measurement and detailed analysis of the espousers of the Attributes called Power and Universalism. (Espousers are those people most inclined to be positive toward a particular attitude or belief).

Using these tools, it is clear that the reaction of the Parliamentary Labour Party and three of the four candidates selected by them is based on a Power dynamic while the one ‘outlier’ - the one who is attracting new, significant and popular support - is based on a Universalism dynamic.

When two scalar and polar opposites clash within a single entity – usually an organization, but it could also be within a movement or indeed a whole country – we have called the phenomenon the ‘logjam of violent agreement’.

In Labour’s case there is a logjam between those who believe that leadership is about gaining power through core policies (that do good for people) and those who believe it is about selecting good people to develop good policies for people: or to put it another way, one dynamic is driven by the attainment and exercise of power and the other acknowledges that power in a democracy should come from popular support for policies that are good for people.

For the Labour Party elite, its former grandees and the current Parliamentary Labour Party it seems that the attainment of power is more important than selecting a Universalist representative – and the grassroots are saying something very different.

From a research perspective there is no right or wrong – but there is a clear and divisive ‘values war’ dynamic at work within the organization. It is this analysis that national and activist media is currently missing – an evidence based model with which to examine the data being collected from various sources.

It is this lack of a ‘values lens’ that, we suggest, creates some of the moral and ethical dilemmas facing centre-left national and specialist publications. Their own versions of group polarization hamper them when they report and comment on the Universalist orientations - of openness, justice, benevolence towards others, and just plain old ‘fairness’ -that characterize the broad based movement piling into the fee-paying segment of the Labour Party selectorate.

This orientation is spread across all traditional demographic groups and, to be fair to party strategists, accounts only for about one third of the population. However, given the nature of the appeal of Universalism (typified as True Labour in an earlier article) it is also very capable of being leveraged into both the Blue Labour and New Labour supporter base. This is good news for strategists but bad news for supporters of the Power dynamic, as it contradicts their world view and sparks resistance – at a deep values led and emotional level. Commentary has postulated that Labour is having ‘a nervous breakdown’: extreme reaction follows deep emotion.

Right-click and select "View Image" to see a larger version.

Interestingly, much modern management theory and, indeed, Sunstein’s conclusions about the efficacy of having diverse options come together to create more robust decisions, is seen as a Universalist solution as opposed to the ‘Winners and Losers’ dynamic inherent in the Power values set. Labour supporters will soon be able to know where the next round of re-evolution will begin.

Whatever the result of the upcoming selection process Labour can look forward to ‘vigorous debate’ in the coming years based on the values wars stimulated by a change in the leadership selection policy.

Later this year we will looking at these dynamics and how they play out in the other major economies of Europe and the impact they have on the politics of France, Germany, Italy and Spain.